XKCD is one of my favorite web-comics, and though most of them are humorous in nature, some of the early ones seem to be more philosophical. This is particularly true of the barrel series. I recommend you read it and think of your own opinions on it before you read my musings on it so that you may develop your own thoughts rather than simply taking in mine.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Important aside

Part 5

Did you read it? They are all really short, so you may as well. They always confused me a bit, until one of my friends pointed out that they are meant to be meaningful, not funny. Thus I began to think about them, and these are the conclusions I came to. I present them to you strip by strip. Note that these are only my thoughts on these strips, and I do not by any means think that my opinion is the only correct one. Feel free to present your own opinion in the comments.

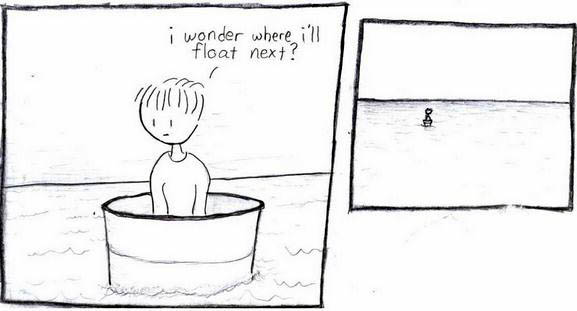

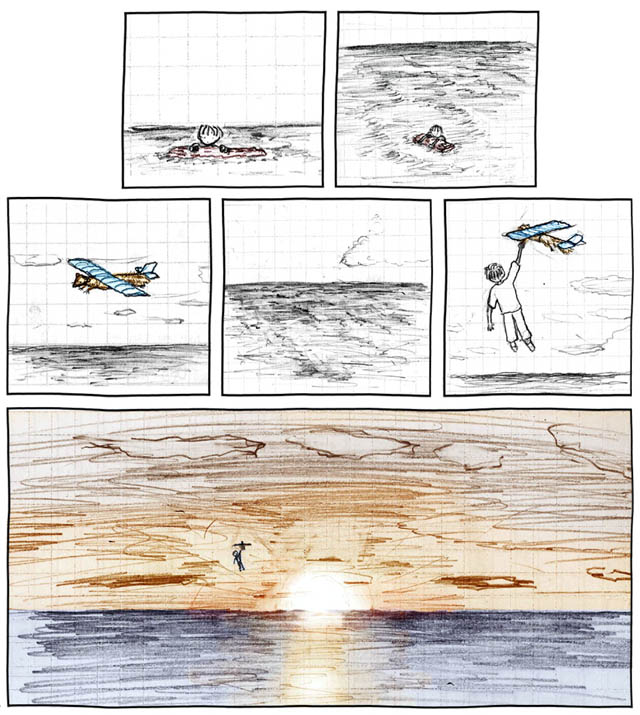

Thus our nameless protagonist starts on his adventure. The fact that he is never named means he could be anyone, and thus any of the trials he faces in his adventure could be faced by any of us. You will notice that proper capitalization is never used in this first strip. This represents a sort of rejection of society's conventions, or at least those of academia. And yet, after rejecting these conventions, our protagonist finds himself utterly alone in a vast expanse of sea. Perhaps the conventions that he rejected now seem to him to be something that connected him to the people around him. His face shows a lack of emotion, which to me shows that he must be feeling equal parts happiness and sadness. After all, how could someone lost in the ocean in a barrel not be at least nervous? Thus I think that he is happy that he is now free from the conventions that he rejected, but now realizes that they were simply part of the social system he too was a member of. By rejecting this system, he has rejected everyone else in his life.

Our protagonist now has only one option, and that is to abandon his society and wander. Without this familiar world, however, all he can do is wonder where he will float to next. What is interesting is that the panel of him lost in the sea is smaller than the panel of him wondering where he will float next. Perhaps the message in this size inconsistency is that it is more important to wonder where your life is going than it is to actually go there. After all, our protagonist has lost all that he knew with his rejection of society, and this society is now part of his past. He has thus rejected his past, and can now only look to the future. The future, however, is not guaranteed to be any better than his past. This is why his floating is trivialized by the size of the panel; it's not something he should actually look forward to. As we shall discover, the future can be fraught with danger and sadness.

One could interpret this to mean simply that there were no mothers where our protagonist floated, but I see more meaning in that. While he could mean there were no mothers in the places he floated to, I think it means that the places themselves had no mothers. I mean mother in more of the sense of a creator than the sense of a woman with a child. And who supposedly created all the places in the world? God. Thus, our protagonist has rejected not only his society but also his God.

You may think I am reading into this too much, but think about it. The protagonist makes his statement with a lot of certainty. None of the places he floated to had mommies; not a single one. That could not be a coincidence, and thus the only possibility is that there are no mommies in his world. This could also be simply a consequence of his rejection of society, but if this were the case, it would not be as much of a surprise to him, and he wouldn't feel the need to state that there were no mommies where he floated.

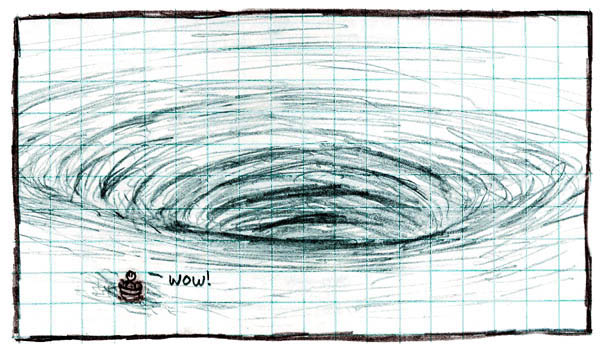

Staring into the abyss, our protagonist can see his inevitable demise, and yet he shows no worry; he is simply amazed by what he sees. It is important to realize at this point that our protagonist has abandoned his society and his God. Left floating in an endless sea, he has nothing to live for. My guess is that this is why he finds his doom interesting; if his life isn't worth living, then he may as well simply enjoy whatever it brings to him, even if it it brings him his own demise.

Staring into the abyss, our protagonist can see his inevitable demise, and yet he shows no worry; he is simply amazed by what he sees. It is important to realize at this point that our protagonist has abandoned his society and his God. Left floating in an endless sea, he has nothing to live for. My guess is that this is why he finds his doom interesting; if his life isn't worth living, then he may as well simply enjoy whatever it brings to him, even if it it brings him his own demise.Of course, a maelstrom is no guarantee of death. People have survived them before, if not in reality, at least in fiction. Thus it is also possible that our protagonist is amazed simply because he knows he could survive the experience. And what an experience it would be; I can't even begin to conjecture on what it must be like to be sucked into a whirlpool, but it would certainly make a good story at the very least. If this is the case, then the larger lesson is that we should not fear that which may kill us. We could end up with an amazing story afterwards, or we may just be exaggerating the dangers. And if worst comes to worse, well, you can't really regret anything that kills you, can you?

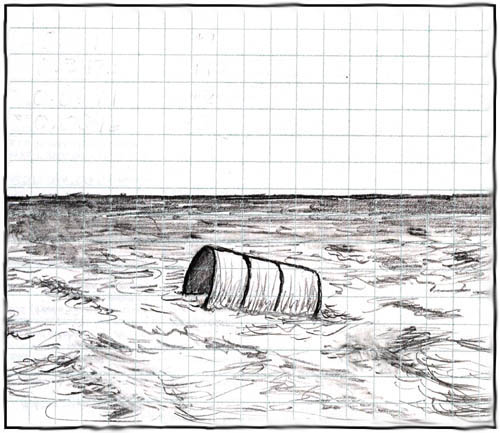

At this point, the fate of our protagonist is unknown. We are left only with an image of his barrel floating semi-submerged in the water. It will probably sink at some point, disappearing from our protagonist's world forever. If he is still alive, he has now lost his only connection to his former world. In a way, this barrel was his world, and now it is on its way to a watery grave. In my opinion, this is meant to symbolize how when a man is removed from a world he has created, that world falls apart, and he cannot return. If our protagonist had made the ocean itself his home, he would still have a home to return to upon escaping the whirlpool. Instead, he tried to create his own artificial world, even while trying to escape the normal world. Now that he no longer has his barrel, he cannot return to it.

In a way, the barrel is symbolic of everything people try to do to make their lives easier. These include developing a Peter Pan complex, trying to shut out the tragedy in the world by avoiding the news, or using the idea of an afterlife as a way to not fear death. Often people do this because they find reality too difficult to deal with. Like the barrel our protagonist inhabited, these coping mechanisms are unreliable and can't protect people from the harsh realities of the world forever. At some point, these people are going to have to face the reality that they have been so diligently avoiding. And once they have done that, their old world and their old coping mechanisms will be gone. Having abandoned them, these people will now need to find some way to face the realities of existence without getting depressed. Life may be grim, but that doesn't mean that people need to be.

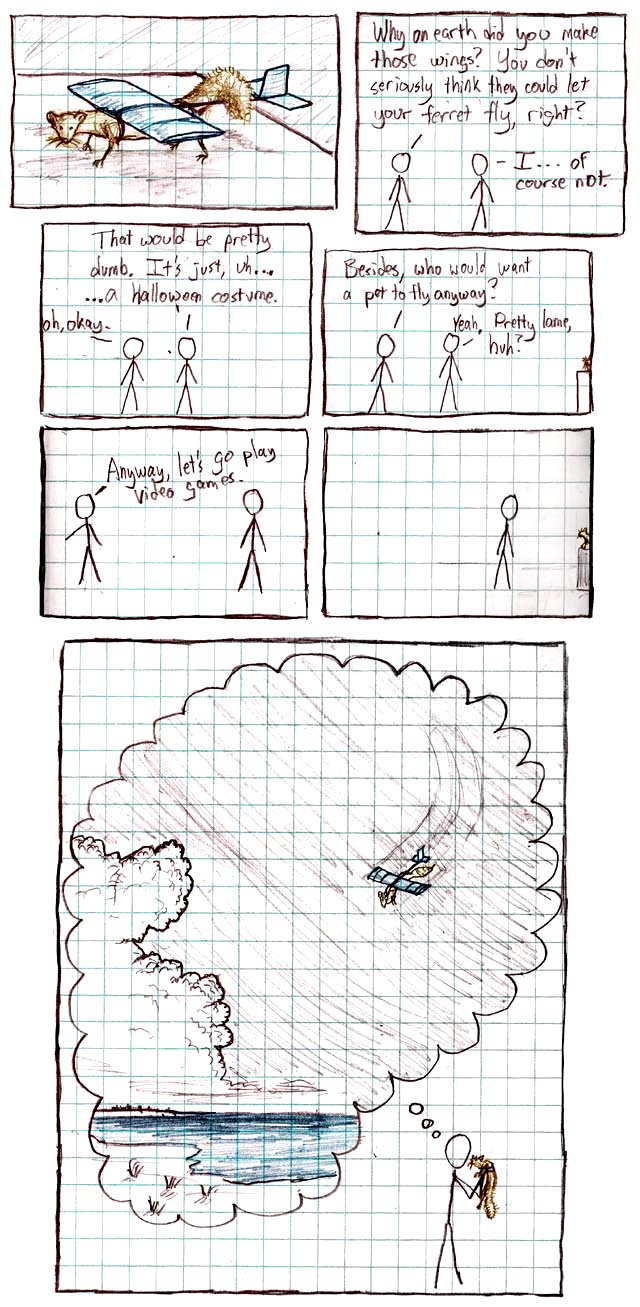

Although this strip is not technically a part of the barrel series, it still plays into the series's conclusion, and thus warrants analysis. We begin with a man who has whimsically put wings on his ferret, but his whimsy is ruined when his friend tells him his ferret could never fly. He is quick to assimilate to his friend's ideas of what is reasonable, not wanting to look silly. What is interesting is that the man's friend dismisses his fantasy and then suggests that they go indulge in a different kind of fantasy, i.e. video games. Perhaps his friend views video games as less silly than imagination because the fantasy is not his own, but someone else's. In other words, this man believes that having your own fantastic ideas is silly, but reveling in someone else's fantasy is perfectly acceptable. Then again, this man could be playing a realistic video game, in which case he simply rejects all forms of fantasy.

In the end, the first man forgoes playing video games in favor of indulging in his own fantasy of seeing his ferret fly over a lake. The proximity of their faces in this final panel suggests a great intimacy between them. Anyone who has ever felt that intimate with anyone, be it a person or an animal, can attest that it is a great feeling. One feels safe, comfortable, and happy when he or she is that close to someone, physically and/or emotionally. It's quite possibly the greatest happiness one can achieve. The message of this intimacy is that there is more happiness to be found in one's own fantasy than the fantasies of someone else.

And so we see our protagonist left drifting on a piece of wood in the vast expanse of ocean. The wood itself is probably of little comfort to him, since he is still submerged in the water. Then in flies our furry little winged friend to save him and they both fly off into the sunset. A touching ending, really. More important is the message of it, and I believe that message is that we can only be saved by our dreams. As we learned in part 4, most coping mechanisms for dealing with life's harsh realities don't work. The problem that these mechanisms have in common is that they all deal with shutting out part of the world. Dreams, on the other hand, deal not with blocking out what is but with imagining what could be. That is why our protagonist is saved by the ferret.

If you think I read too deeply into those comics, your probably right. Of course, considering the wealth of philosophical possibility in them, I'd like to imagine that Randall Munroe intended them to be analyzed in this manner.

No comments:

Post a Comment